From The New York Times Online...

Anne Bancroft, Actress Who Played Mrs. Robinson, Is Dead at 73

By ROBERT BERKVIST

Published: June 7, 2005

Anne Bancroft, enshrined in film history as the iconic Mrs. Robinson, the seductress who devours her daughter's nerdy boyfriend-to-be (Dustin Hoffman) in the 1967 film "The Graduate," and also remembered for her sensitive portrayal on both stage and screen of Annie Sullivan, the teacher who leads the blind and deaf Helen Keller out of darkness into light in "The Miracle Worker," died Monday at Mount Sinai Medical Center. She was 73.

The cause was uterine cancer, said John Barlow, a spokesman for the family.

Those widely dissimilar roles were emblematic of Ms. Bancroft's long career. During more than 50 years of acting in films, theater and television she played everything from Brecht's "Mother Courage" to the mother superior of a convent, and from an aging ballerina to the Prime Minister Golda Meir of Israel, and repeatedly won praise for her work. Arthur Penn, who directed her award-winning Broadway performances in "Two for the Seesaw" and "The Miracle Worker," both by William Gibson, put it this way: "More happens in her face in 10 seconds than happens in most women's faces in 10 years."

Ms. Bancroft worked hard to get beneath the surface, to inhabit a role as deeply as possible. While rehearsing for "The Miracle Worker," she put tape over her eyes to better understand what it was like to be blind like Helen Keller, learned sign language and spent time at a home for the visually impaired. Preparing for "Golda," she traveled to Israel and got to know and observe Prime Minister Meir. She was more interested in performance than theory, although she was a member of the Actors Studio early in her career. The actor Rod Steiger once gave her a copy of Stanislavsky's writings on acting. "I still have it," she said some years later, "but I've never read it."

The landmarks in Ms. Bancroft's acting life were, unquestionably, the two Gibson plays and "The Graduate." She had already accumulated a long list of credits in TV dramas when she moved to Hollywood in the early 1950's to join the crowd of young hopefuls jostling for jobs in second- or third-rate films. She was among the few who found steady work, appearing in more than a dozen grade-C features with titles like "Treasure of the Golden Condor," "Gorilla at Large" - "I played the title role" - and "Demetrius and the Gladiators." Disenchanted after five years or so, and newly divorced, she headed back to New York with the promise of an audition for a new Broadway play called "Two for the Seesaw."

It was a two-character play, with Henry Fonda starring as a depressed Midwestern lawyer with marital troubles who comes to New York and meets Gittel Mosca, an attractive, thoroughly quirky young bohemian girl from the Bronx. They are two lost souls who, though their lifestyles are worlds apart, manage to help one another. Ms. Bancroft, who happened to be not only attractive and quirky but also Bronx-born and raised, auditioned and got the job. After a rocky start - she had virtually no stage experience - she quickly settled into the role. When the play opened in 1958, Ms. Bancroft stole the show and ultimately won a Tony Award as best supporting actress.

When the next Gibson-Penn theater project took shape the following year - the story of Helen Keller and her teacher Annie Sullivan - they knew who would play Sullivan from day one. The part of the hostile, 10-year-old Helen went to Patty Duke. Between them, Ms. Bancroft and Ms. Duke tore up the stage as Sullivan struggled to communicate with and calm her raging young charge, eventually breaking through the child's defensive shell. "The Miracle Worker" was a resounding hit, and Ms. Bancroft came away with her second Tony Award, this time as best actress. Tonys also went to Mr. Penn, Mr. Gibson and the play's producer, Fred Coe. Two years, two plays, two Tonys. And when "The Miracle Worker" was made into a film in 1962, both Ms. Bancroft and Ms. Duke won Academy Awards.

Hollywood now had a new star, and Ms. Bancroft was offered scripts rather better than, say,

"Gorilla at Large." She appeared with Peter Finch in "The Pumpkin Eater" (1964), Harold Pinter's adaptation of a novel by Penelope Mortimer about a woman driven into a nervous breakdown by her husband's casual philandering. Her work brought her an Oscar nomination. Next came "The Slender Thread" (1965), in which she played a housewife whose crumbling marriage leads her to attempt suicide.

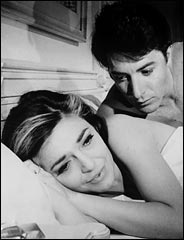

By the time "The Graduate" came along, she was more than ready to play the alpha female and she got her wish with the character of Mrs. Robinson of Beverly Hills, the bored predator whose sexual binges with young Ben Braddock, the son of her husband's law partner, are mechanical but necessary props for her self-indulgent ego. Directed by Mike Nichols, with a melancholic soundtrack of songs by Simon and Garfunkel, "The Graduate" was hailed as a winning social satire. Bosley Crowther, writing in The New York Times, called it "devastating and uproarious" and hailed Ms. Bancroft's "sullenly contemptuous and voracious performance." Mr. Nichols won an Oscar, while nominations went to Ms. Bancroft, Mr. Hoffman and Katharine Ross, who played Mrs. Robinson's daughter. The still photograph that appeared in advertisements for the film, showing Mrs. Robinson slowly peeling off a nylon stocking under the glazed gaze of Mr. Hoffman's Ben Braddock, became a classic of its kind.

More good roles lay ahead, but Ms. Bancroft had definitely hit a high point.

Anna Maria Louisa Italiano was born Sept. 17, 1931, in the Bronx to Italian immigrant parents. Her father, Michael, was a patternmaker, and her mother, Mildred, a telephone operator. By the time she was 2 years old she was learning to sing and dance. "Why play with dolls," she recalled years later, "when you can sing 'I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate' on the street corner?" Even so, by the time she left high school she had decided to become a laboratory technician. Instead, her mother insisted she attend the New York Academy of Dramatic Arts. Two years later she found work in television where, as Anne Marno, she appeared in scores of dramatic shows. In 1951 she was asked to participate in another actor's screen test for 20th Century Fox, after which she, not he, was offered the contract that took her to Hollywood. At the studio she was handed a book of names and urged to choose a new one. She became Anne Bancroft. She had no illusions about that chapter of her film career, noting some years later that "20th Century Fox told me what to do and I did it. I learned nothing."

During her first stay in Hollywood she married Martin A. May, a building contractor, in 1954. They were divorced in 1957. In 1964 she married Mel Brooks, who survives her along with their son, Maximilian, and grandson.

The 1970's and 80's saw Ms. Bancroft take on a wide variety of roles, from Winston Churchill's American-born mother in "Young Winston" to the actress-wife of a hammy Polish impresario ("world famous in Poland"), played by Mr. Brooks, in the farcical "To Be or Not to Be." She also earned two more Oscar nominations, one for her portrayal of a ballerina confronting her choice of career over family in "The Turning Point," the other for her work as a mother superior in "Agnes of God." Other major roles included "'Night Mother," as a woman struggling with her daughter's decision to commit suicide, and "84 Charing Cross Road," in which she played an American writer whose correspondence with a London bookseller (Anthony Hopkins) develops into a long-distance romance.

She rarely returned to the theater, although she did win praise as the steel-willed Regina Giddens in Mr. Nichols's 1967 staging of Lillian Hellman's "Little Foxes" at Lincoln Center. In The Times, Clive Barnes characterized her performance as "a series of unforgettable visual and aural images." The following year Ms. Bancroft appeared in the Lincoln Center Repertory production of another William Gibson drama, "A Cry of Players," set in Shakespearean England. Her performance in "Golda" (1977) brought her a Tony nomination. She played a crippled violinist in the 1981 "Duet for One," which closed after a two-week run, and then was absent from the stage until the spring of 2002, when she was set to star in Edward Albee's "Occupant" as the sculptor Louise Nevelson. The play's scheduled run had to be canceled when Ms. Bancroft contracted pneumonia during previews.

In later years she continued to appear in films, although the roles grew smaller. She was briefly on screen as Nicolas Cage's mother in "Honeymoon in Vegas," trained a young woman as an assassin in "Point of No Return," scored a few points as a wily senator in "G.I. Jane" and had some campy fun in an updated version of "Great Expectations" as a loony character based on Dickens's Ms. Havisham.

She fared better in television, earning Emmy nominations playing a killer in the PBS drama "Mrs. Cage" and the title role in "Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All" on CBS.

She was resigned to the fact that age and changing times worked against her. In a 1992 interview with The Times's Bernard Weinraub she admitted to taking parts "even if they're one page," because "there are very few good scripts, even for Julia Roberts." She preferred a good bit part to a heftier bad one. She often rejected work in favor of family life - for a while. "I retire after every project," she once said. "Then somehow there's always something that pulls me out of retirement."

1 comment:

Holy...how the hell did she get to be 73?

I am flummoxed by Father Time once again :(

Post a Comment